Since the outbreak of the war, the Royal Navy was trying desperately to bring the German East Asia Squadron under their guns before Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee could begin commerce raiding. Working with the Japanese, the British discovered that von Spee was heading for the Chilean port city of Coronel. A Royal Navy squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was dispatched to stop the German squadron.

Before the Battle

The German East Asia Squadron under command of Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee began the war based at Tsingtao in China. This force consisted of the armored cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and three modern light cruisers, Dresden, Leipzig and Nurnberg. After abandoning his base due to the Japanese siding with the British, von Spee decided to conduct commerce raiding along the crucial trading routes along the west coast of South America. Patrolling these waters was Admiral Cradock's West Indies Squadron, consisting of two armored cruisers, HMS Good Hope (Cradock's flagship) and HMS Monmouth, the modern light cruiser HMS Glasgow, and a converted liner, HMS Otranto, waiting to pounce.

A Series of Misunderstandings

Seeking information on the German squadron’s whereabouts, Cradock dispatched the light cruiser Glasgow from his base in the Falklands to Coronel to gather intelligence. Upon hearing the news of Glasgow’s departure for Coronel, von Spee set sail from Valparaíso with his entire squadron with the intention of destroying her. Back in the Falklands, Cradock knew that his squadron was out gunned and pleaded for reinforcements. The Admiralty sent the armored cruiser Defence and the pre-dreadnought battleship Canopus. Neither would arrive in time. Cradock sailed for Coronel

On October 31, Glasgow arrived at Coronel to gather messages and news from the British consul. Upon entering the harbor, the supply ship Gottingen, reporting to Spee, signaled the arrival of the Glasgow to Spee. Spee hoped to catch the British cruiser leaving port and sink her. While Spee and the Gottingen were talking, the Glasgow was listening, now knowing that German warships were in the area. Unknown to the Glasgow, Spee had ordered all of his ships to use the call sign of the Leipzig. The British ship reported to Cradock that the Leipzig was in the area. Upon receiving this information, Cradock increased speed to catch the lone German cruiser. So, while Cradock was steaming up from the Falklands and Spee was in route from Valparaíso, neither admiral knew that an enemy squadron was approaching.

The Battle

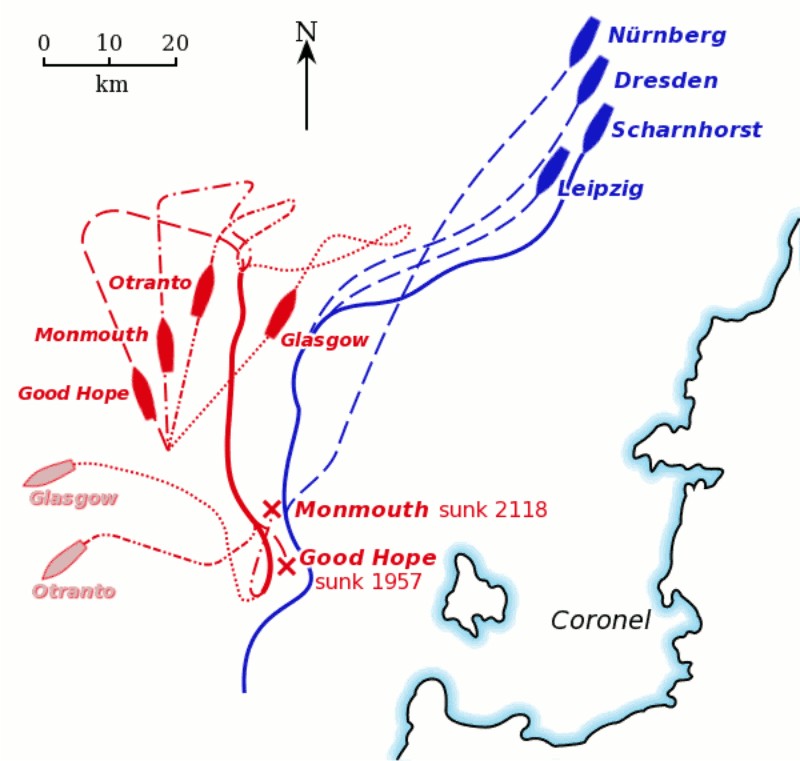

On the morning of Nov. 1, the Glasgow set sail to rendezvous with Cradock’s force 40 miles west of Coronel. In heavy seas, the British West Indies Squadron formed into a battle line 15 miles apart and set off to the north to search for the Leipzig. Shortly after 4:00 p.m., the German squadron sighted the smoke of Cradock’s force and increased speed; they were closing upon the British at 20 knots. Three minutes later, the Glasgow and the Otranto spotted the Germans’ smoke and Cradock, now realizing that facing the entire German squadron reversed course. Both forces were now heading south. The chase was on.

Cradock had a tough decision to make. Does he take his three cruisers, each capable of 20 knots, and run for it abandoning the slower Otranto or does he turn and fight, knowing the at converted liner stood little chance against the German ships. At this crucial time in the battle, Spee, just 15,000 yards from the British, slowed to reorganize themselves and await better visibility.

At this point, Cradock could have made a run to the south in order to meet up with the Canopus, just 300 miles to the south. In the late afternoon and evening light, Spee would have lost contact before he was in range. At 5:10, Cradock chose to stay and fight, reversing course and sending the slower Otranto fleeing. Cradock sought to attack with the sun at his back, thus interfering with the German gunners’ ability to aim. Spee turned his force away and ran a parallel course to Cradock at a range of 14,000 yards. An hour later, Cradock turned directly for the enemy who turned away and increased the distance to 18,000 yards. When the sun set and Cradock was now at a disadvantage, Spee closed to a range of 12,000 yards and commenced firing.

Within 5 minutes of the start of the German bombardment, the Good Hope, Cradock’s flagship, had on of it’s 9 inch guns silenced and thus limiting the British fire power to one 9 inch gun to the Germans’ sixteen 8 inch guns. At 7:30 p.m., the British had closed to a range of 6000 yards in order to unleash their 6 inch guns onto the German ships. However, the German accuracy improved at the reduced range, setting fires raging on both the Good Hope and Monmouth. The Monmouth was the first ship knocked out with the Good Hope not far behind. At 7:50, the Good Hope ceased to fire, broke apart and sank.

With the Good Hope gone, the Scharnhorst switched firing towards Monmouth, while Gneisenau joined Leipzig and Dresden in engaging Glasgow. The German light cruisers, armed only with 6 in guns, was having little impact on the Glasgow. The Gneisenau’s 8 inch guns were another matter. With both British armored cruisers out of action, the captain of the Glasgow turned his ship towards the Otranto and retreated, living to fight another day.

In the confusion of the battle, the fate of the British armored cruisers were unknown to the Germans. The Good Hope had disappeared. The slower Nurnberg, just reaching the battle, sighted Monmouth, listing and badly damaged but still moving. After pointedly directing their searchlights at the ship's ensign, an invitation to surrender which was declined, the Nurnberg opened fire, finally sinking the ship. Having reports that a British battleship was in the area, Spee, believing that the Good Hope had escaped, turned his force to the north and retired.

Aftermath

The British West Indies Squadron had lost both armored cruisers, Good Hope and Monmouth, with no survivors. The Glasgow and Otranto both escaped, the Glasgow suffering minor damage and no deaths. The German East Asia Squadron faired much better. Just two shells had struck Scharnhorst, neither of which exploded, whereas she had managed at least 35 hits on Good Hope. Four shells had struck Gneisenau, but had done little damage. The only down side for the Germans was that the battle had exhausted half of their ammunition, something that could not be replaced.

Sources:

Wikimedia Commons

Wikipedia

First World War.com