BOA - Weapon of the Week - U-48

From U-boat.net, Wikipedia and the Hofnaflus Teo website (http://www.iol.ie/~hofnanet/index.html)

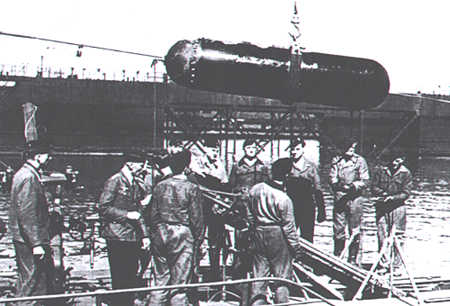

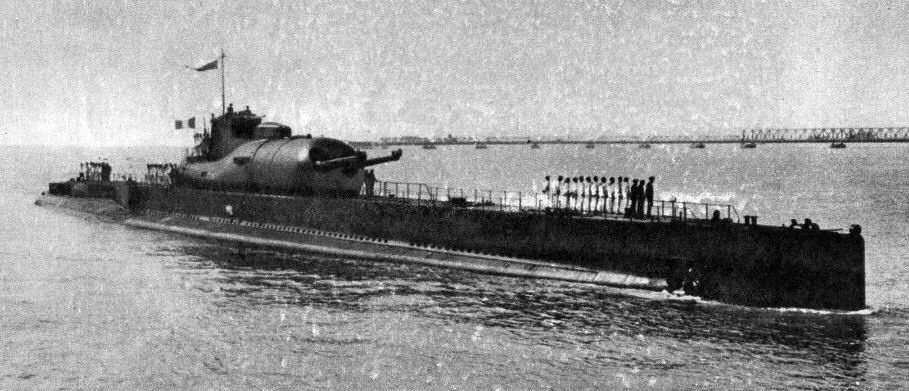

German submarine U-48 was a Type VIIB U-boat and the most successful that was commissioned. During her two years of active service, U-48 sank 55 ships for a total of 321,000 tons; she also damaged two more for a total of 12,000 tons over twelve war patrols conducted during the opening stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

U-48 was built at the Germaniawerft in Kiel as Werk 583 during 1938 and 1939, being completed a few months before the outbreak of war in September 1939 and given to Kapitänleutnant (Kptlt.) Herbert Schultze. When war was declared, she was already in position in the North Atlantic, and received the news via radio, allowing her to operate immediately against Allied shipping.

She was a member of two wolf packs. Seven former crew members of U-48 earned the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross during their military career, these were the commanders Herbert Schultze, Hans-Rudolf Rösing and Heinrich Bleichrodt, the first watch officer Reinhard Suhren, the second watch Otto Ites, the chief engineer Erich Zürn and the coxswain Horst Hofmann.

U-48 survived most of the war and was scuttled by her own crew on 3 May 1945 off Neustadt in order to keep the submarine out of the hands of the advancing allies.

U-48 left her home port of Kiel on 19 August 1939, before World War II began, for period of 30 days. The submarine travelled north of the British Isles, into the North Atlantic and eventually into the Bay of Biscay. She then proceeded to cruise to the west of the Western Approaches, two days after Britain and France declared war on Germany. It was here that she spotted her first target, the 5,000 ton SS Royal Sceptre. U-48 attacked the merchant ship with her deck gun on 5 September 1939. All of the crew took to the lifeboats except the Radio Officer who remained transmitting "SOS". He was taken prisoner by U-48, but then released to the lifeboats as Schultze praised his courage. He verified that the lifeboats were provisioned with food and water. U-48 then stopped the SS Browning. The crew abandoned their vessel, but Schultze told them to return to their ship and pick up the crew of Royal Sceptre. However Browning was en route to Brazil, so it was not immediately realised that they had survived. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of The Admiralty, assumed the worst, that the crew and sixty passengers were lost. He declared the sinking to be

“ an odious act of bestial piracy on the high seas ”

U-48 stopped, searched and released several neutral ships before encountering and sinking Winkleigh on 8 September 1939 after her crew had taken to the lifeboats.

On 11 September U-48 sank the Firby. Some of the crew required medical attention following the sinking. U-48 provisioned the lifeboats, gave medical assistance and radioed:

“ Transmit to Mr Churchill. I have sunk the British steamer Firby. Posit 59°40'N 13°50'W. Save the crew if you please. German submarine ”

Churchill, wrongly, told the House of Commons that the U-boat captain who had sent the message had been captured. After 30 days at sea, U-48 returned to Kiel on 17 September 1939. During her first war patrol, she sank three ships for a total of 14,777 tons.

2nd patrol (4–25 October 1939)

U-48's second patrol was even more successful. Having left Kiel on 4 October, she proceeded to follow the same course as her previous voyage. During her second patrol, U-48 sank a total of five enemy ships, including the large French tanker SS Emile Miguet on 12 October, Heronspool and Louisiane on 13 October, Sneaton on 14 October and Clan Chisholm on 17 October. Following the sinking of the Clan Chisholm, U-48 attacked the British steamer Rockpool with fire from her deck gun on 19 October at 1:32 pm. However, the steamer returned fire. In order to avoid being hit, U-48 crash-dived. She subsequently re-surfaced and attempted to sink the steamer again when an Allied destroyer came upon the engagement. U-48 then broke off the fight with the Rockpool and submerged once more to leave the area. Following the sinking of five enemy merchant ships for a total of 37,153 tons as well as the engagement with the Rockpool, U-48 returned to the safety of Kiel on 25 October 1939 after spending 22 days at sea.

3rd patrol (20 November – 20 December 1939)

U-48 left Kiel for her third patrol on 20 November 1939. During this voyage, she sank a total of four vessels including two merchant ships from neutral nations. The first ship to fall victim to the U-boat was the 6,336-ton neutral Swedish motor tanker MT Gustaf E. Reuter. She was attacked by U-48 on 27 November 14 nautical miles (26 km; 16 mi) west-northwest of Fair Isle. The wreck was later sunk by an escort vessel. One person died, 33 of her crew survived. The tug HMS St. Mellons attempted to salvage her, however the Gustaf E. Reuter eventually had to be sent to the bottom by HMS Kingston Beryl on 28 November. Following the sinking of the Gustaf E. Reuter, U-48 sank the British freighter Brandon on 8 December off the southern coast of Ireland. The next day, she attacked the British tanker San Alberto. The ship was so badly damaged that she had to be sunk by HMS Mackay. Finally on 15 December 1939 U-48 stopped the neutral Greek freighter Germaine which had been chartered by Ireland and was also neutral, to carry maize to Cork. Schultze maintained that she was going to England, so he sank her. U-48 returned to Kiel on 20 December 1939 after sinking a total of 25,618 tons and spent a total of 31 days at sea.

4th patrol (24 January – 26 February 1940)

After a break over the Christmas period, the boat put to sea again, sinking the British Blue Star Line liner SS Sultan Star in the Western Approaches, it was only carrying freight. She laid a string of mines off St Abb's Head which failed to have any effect, but two neutral Dutch ships were added to her tally shortly afterwards, as well as a Finnish ship, all of them operating in the North Atlantic in cooperation with the Allied convoy system.

5th and 6th patrols (April 1940 and June 1940)

Her fifth patrol, in June 1940 was one of her most successful, making full use of the situation in Europe following the Fall of France. U-48 was commanded by Hans Rudolf Rösing, as Herbert Schultze was hospitalised with a kidney and stomach complaint. She attacked three ships off the Donegal coast; the Stancor carrying fish from Iceland, the Eros carrying 200 tons of small arms from America and the Frances Massey with iron ore. 34 sailors lost their lives on the Frances Massey. The cargo on the Eros was particularly important following the losses at Dunkirk. The badly damaged Eros was taken in tow by HMS Berkeley, assisted by HMS Bandit and Volunteer and headed to the Irish coast, where the Muirchú and Fort Rannoch were waiting for them. The Eros was beached on Errarooey strand. While she was being repaired, Irish troops guarded the site.

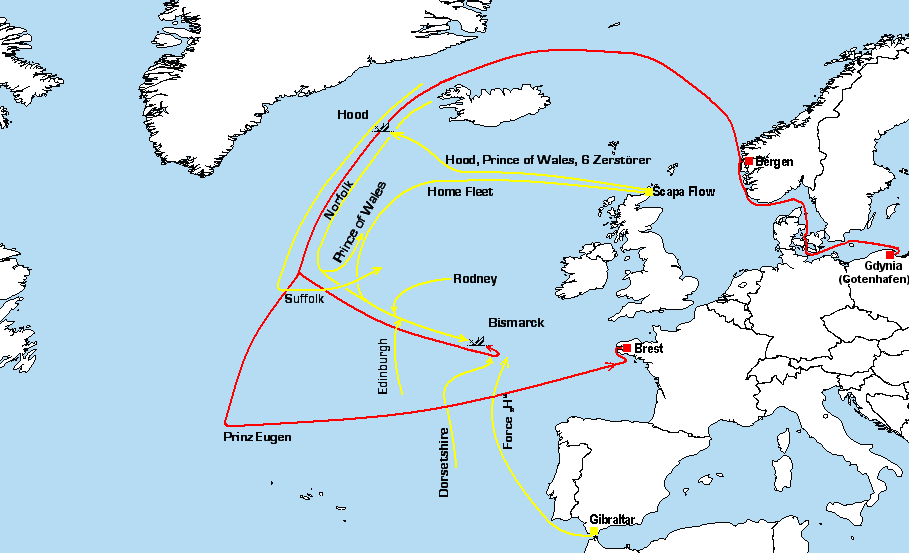

Germany learned that a troop convoy, including RMS Queen Mary and Mauretania were bringing 25,000 Australian soldiers to Britain. U-48 was ordered to Cape Finisterre where a U-boat 'wolf pack' was being assembled to intercept the convoy. However the U-boats attacked other ships in the vicinity, alerting the convoy to their presence, so they altered direction, avoiding the 'wolf pack'. On 19 June 1940, Convoy HG-34 was attacked. U-48 sank SS Baron Loudoun (three died), SS British Monarch (all 40 on board died) and MV Tudor (one death). Convoy HX-49 dispersed; U-48 sank Moordrecht which had been in that convoy; 25 died. Ireland had chartered neutral Greek ships; U-48 sank Violando N. Goulandris (six died) while U-28 sank Adamandios Georgandis (one death). Ireland sought an explanation from Germany "... steamships, the entire cargoes of which comprised grain for exclusive consumption in Éire were sunk by unidentified submarines ..."

U-48 was enjoying an extended patrol, thanks to the newly established refuelling facilities available at Trondheim in Norway. In all, she claimed eight ships from the convoys in the Eastern Atlantic on this cruise and bagged five more on her sixth patrol in August, which finished with her stationed at Lorient on the French Atlantic coast, greatly extending her raiding abilities.

7th and 8th patrols (August 1940 and September 1940)

In September, on her seventh patrol she shocked the world by sinking the SS City of Benares, one of eight ships in six days from Convoys SC-3 and OB-213. Benares was a refugee ship, carrying children from Britain to Canada to keep them safe from the 'Blitz' on Britain's cities. 258 people, including 77 children, died. Among the other sinkings was the British frigate HMS Dundee. The U-boat's eighth patrol was also highly successful, sinking seven ships out of Atlantic convoys, including one from SC-7. The operating zone for both these patrols was far to the north of her previous areas, being south of Greenland.

9th, 10th, 11th and 12th patrols (October 1940, February 1941, March 1941 and June 1941)

On her ninth and tenth patrols, U-48 claimed two and five victims respectively, but she was clearly becoming obsolete in the face of improving technology on both sides, despite a winter refit. Her range and torpedo capacity were too small for the widening nature of the sea war, and she would be a risk to her crew and other U-boats if she continued much longer in the main battlefield of the North Atlantic. On her final patrol she sank five more ships, the boat was also boosted by the award of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross to Erich Zürn, the boat's executive officer, for his success and judgement during the ship's career.

Retirement and fate

U-48 returned to Kiel on 22 June 1941, where her crew disembarked and she was transferred to a training flotilla operating exclusively in the Baltic Sea. Unlike many of her contemporaries, U-48 never sailed on patrols against Soviet targets following Operation Barbarossa the following month. In 1943 she was deemed unfit even for this reduced service, being laid up at Neustadt in Holstein with only a skeleton crew performing minor maintenance. It was there that she remained for the next two years, until the maintenance crew, realising that the war was ending and the boat would be captured, scuttled her in the Bay of Lübeck on 3 May 1945, where she remains.

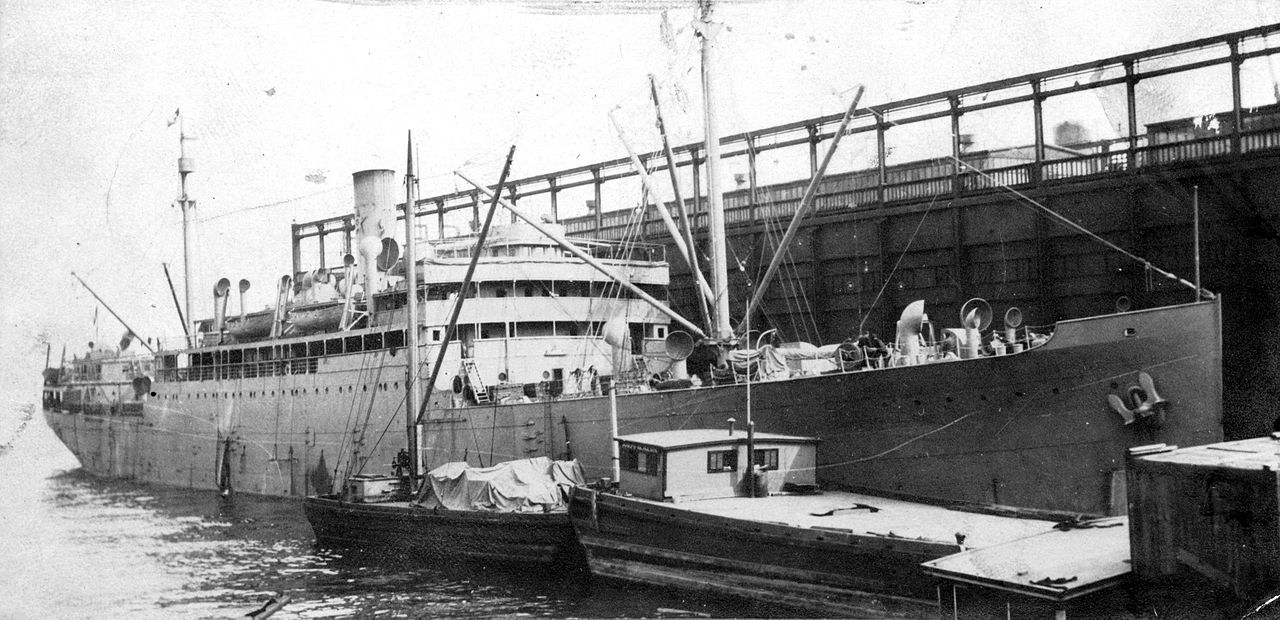

The sinking of the City of Benares

In the late hours of the 17 September 1940, U-48, commanded by Kptlt. Heinrich Bleichrodt, put a single torpedo into the 11,000 ton liner SS City of Benares, flagship of Convoy OB-213, as she was silhouetted against the moonlight in mid-Atlantic. On board the liner were 90 children being evacuated to Canada under the Children's Overseas Reception Board's initiative.

The sinking ship took on an immediate list, thus preventing the launching of many of the life-rafts and trapping numerous crew and passengers below decks. As a result, many of the 400 people on board were unable to escape. As hundreds of survivors struggled in the water, the U-boat's powerful searchlight swept once over the chaotic scene, before she left the area. The survivors in the boats were not rescued for nearly 24 hours. In that time dozens of children and adults died from exposure or drowned, leaving only 148 survivors. One boat was not recovered for a further eight days. In total 258 people, including 77 of the evacuees, died in the disaster, which effectively ended the overseas evacuation programme.

The controversy of the City of Benares disaster has been debated ever since. It has been suggested that had the British openly declared that the ship was carrying evacuees, then the Germans would have taken pains not to sink it, recognising the potential for a propaganda crisis, which indeed occurred. However, the ship was not only travelling unlit at night in an allied convoy, but it was also the flagship of Rear-Admiral Edmund Mackinnon, the convoy commander. Other historians have argued that the Germans would have attacked any large liners at the time, no matter what cargo was being carried or who was on the passenger list.